03 Feb Rethinking Fast Fashion: The Environmental Cost of Cheap Clothes

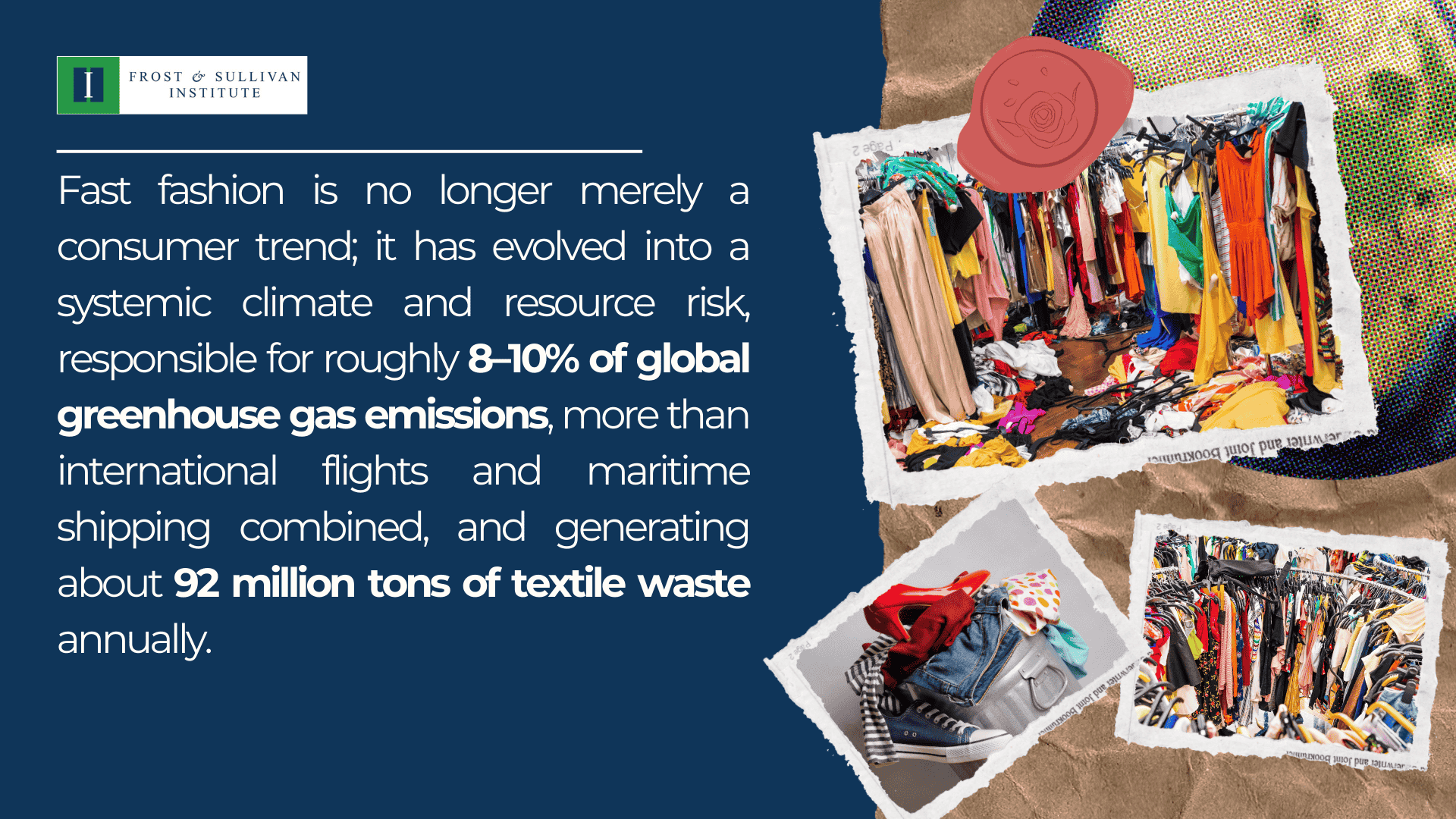

Fast fashion has become a ubiquitous term in the contemporary apparel landscape, denoting a business model that emphasizes the rapid design, production, and distribution of inexpensive garments that mimic current trends. Engineered for speed and scale, these garments are often worn only a handful of times before disposal, embedding waste directly into the logic of fashion itself.

While the industry is often critiqued for its reliance on cheap materials, its most profound environmental damage stems from chronic overproduction: the average garment is worn just 7–10 times before disposal, and less than 1 % of textiles are recycled into new clothing, leaving the rest to clog landfills or be incinerated. Although fast fashion has democratized access to style, making trend-driven apparel affordable to millions, this accessibility comes at a steep ecological cost. Efforts to promote circular fashion are increasingly being presented as solutions, yet without policy pressure and fundamental reform of demand forecasting, such initiatives risk becoming cosmetic fixes that fail to address the core problem of overproduction.

Understanding Fast Fashion

Fast fashion refers to the accelerated production cycle of clothing, driven by consumer demand for ever-changing styles at low prices. Brands and online platforms epitomize this model, releasing frequent collections to sustain high turnover and stimulate relentless consumption. Unlike traditional fashion, which might present a few seasonal collections annually, fast fashion churns out new designs weekly or even daily, prioritizing volume over durability. This accelerated cycle not only encourages overconsumption but also externalizes environmental costs onto ecosystems and communities around the world.

In contrast to the fast fashion model, a growing number of brands are demonstrating that fashion can be both stylish and environmentally responsible by embracing slow fashion and circular economy principles. Companies such as Patagonia and Eileen Fisher prioritize durability, timeless design, and repairability, offering take-back and resale programs that extend garment lifespans. Veja is recognized for its transparent supply chain, fair labor practices, and use of organic and recycled materials in footwear. Meanwhile, brands like Reformation and People Tree integrate sustainable fabrics, low-waste manufacturing, and fair wages into their business models, proving that ethical practices can coexist with commercial success.

Why Fast Fashion Is One of the Biggest Polluters

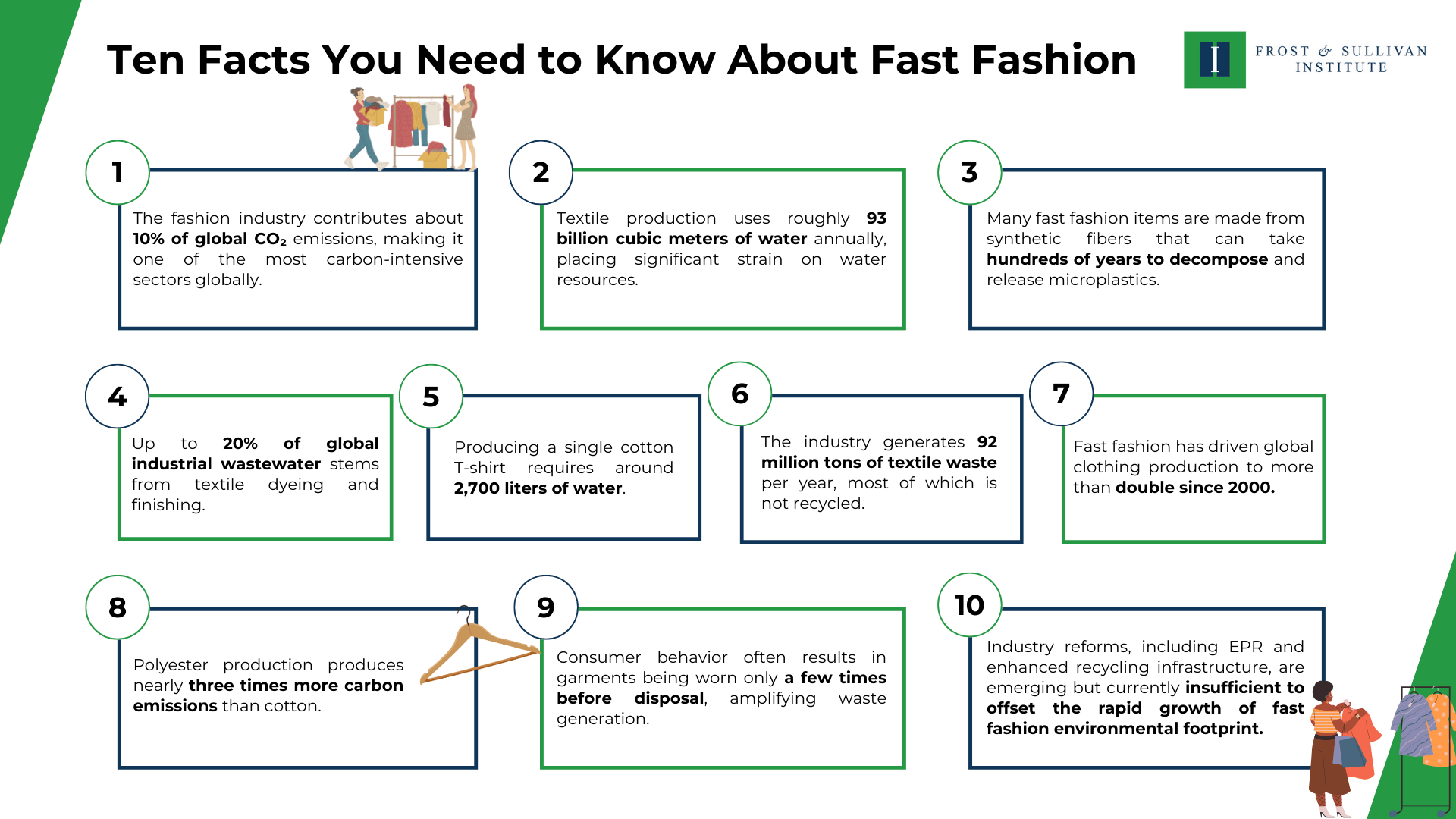

The environmental footprint of fast fashion is profound and multifaceted. At its core, the industry is estimated to contribute roughly 10% of global carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, a figure that rivals or exceeds emissions from international aviation and maritime shipping combined.

The lifecycle of a garment from raw material extraction to production, transportation, use, and disposal is inherently resource-intensive:

- Carbon Emissions: The fashion industry emits an estimated 1.2 billion metric tons of CO₂ equivalent per year, underscoring its significant role in climate change.

- Water Consumption and Pollution: Textile production uses vast quantities of water. Producing a single cotton T-shirt can require around 2,700 liters of water, equivalent to what one person might drink over more than two years. Additionally, dyeing and finishing processes contribute up to 20% of global industrial wastewater, often discharged untreated into rivers.

- Waste and Landfill Overflow: Fast fashion promotes a “take-make-dispose” culture. Approximately 92 million tons of textile waste is generated annually, much of which ends up in landfills or incinerators. Synthetic fibers like polyester and nylon, prevalent in fast fashion, can take centuries to decompose and release microplastics that infiltrate soils and waterways.

Furthermore, polyester production generates nearly three times the carbon emissions of cotton, and synthetic textiles are a significant source of microplastic pollution, accounting for up to 35% of primary microplastics found in oceans. These microplastics are increasingly detected in marine ecosystems, wildlife, and even human food chains, raising long-term health and ecological concerns.

The Urgency of Addressing Fast Fashion’s Environmental Impact

Addressing fast fashion’s environmental cost is urgent for several reasons. First, the scale of production and consumption continues to grow global clothing production has more than doubled since 2000, driven in large part by the fast fashion model. If current trends persist, projections suggest a 50% increase in industry greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, exacerbating global warming.

Second, the depletion of natural resources, particularly freshwater and arable land, undermines environmental resilience, especially in water-stressed regions where cotton cultivation and textile manufacturing are concentrated. Third, the sheer volume of textile waste contributes to overflowing landfills and environmental degradation, with significant implications for soil and water quality.

These impacts are not remote; they compound existing climate, biodiversity, and public health challenges. Therefore, rethinking the fashion industry’s production and consumption paradigms is not merely an ethical choice but a strategic necessity for sustainable development.

Mitigating the Environmental Cost of Fast Fashion

Addressing the environmental cost of fast fashion requires integrated interventions across policy, industry, and consumer behavior. Solutions must shift the industry from a linear “take-make-dispose” model to more circular and sustainable practices.

- Policy and Regulation: Governments and supranational bodies can mandate extended producer responsibility (EPR), requiring brands to manage the end-of-life impact of their products. The European Union, for example, is advancing regulations to obligate textile producers to bear responsibility for garment waste collection and recycling by 2030, a move that could reshape fast fashion economics if widely adopted.

- Industry Innovation: The adoption of sustainable materials, renewable energy in production, and investments in advanced textile recycling technologies are critical. Innovations in automated sorting and AI-enabled recycling infrastructure can enhance the scalability of circular practices, reducing reliance on virgin resources, and diverting waste from landfills. Supply chain optimization and predictive analytics may also reduce overproduction and align manufacturing with actual demand rather than speculative fashion cycles.

- Consumer Behavior: Consumers play a vital role in valuing quality over quantity, extending garment lifespans through repair and reuse, and participating in resale or rental economies. Reducing consumption frequency and supporting brands with transparent sustainability commitments can collectively reduce environmental pressures.

Conclusion

Fast fashion’s environmental costs are vast, encompassing carbon emissions, water depletion, pollution, and waste generation at scales that challenge planetary boundaries. While affordable clothes have undeniable social and economic benefits, current production and consumption patterns are unsustainable. Addressing this crisis necessitates coordinated policy frameworks, technological advances, industry commitment to circular models, and conscious consumer behavior. Only through systemic change can the environmental toll of cheap clothes be reduced, enabling a fashion industry that respects both people and the planet.

Blog by Shreya Ghimire,

Research Analyst, Frost & Sullivan Institute