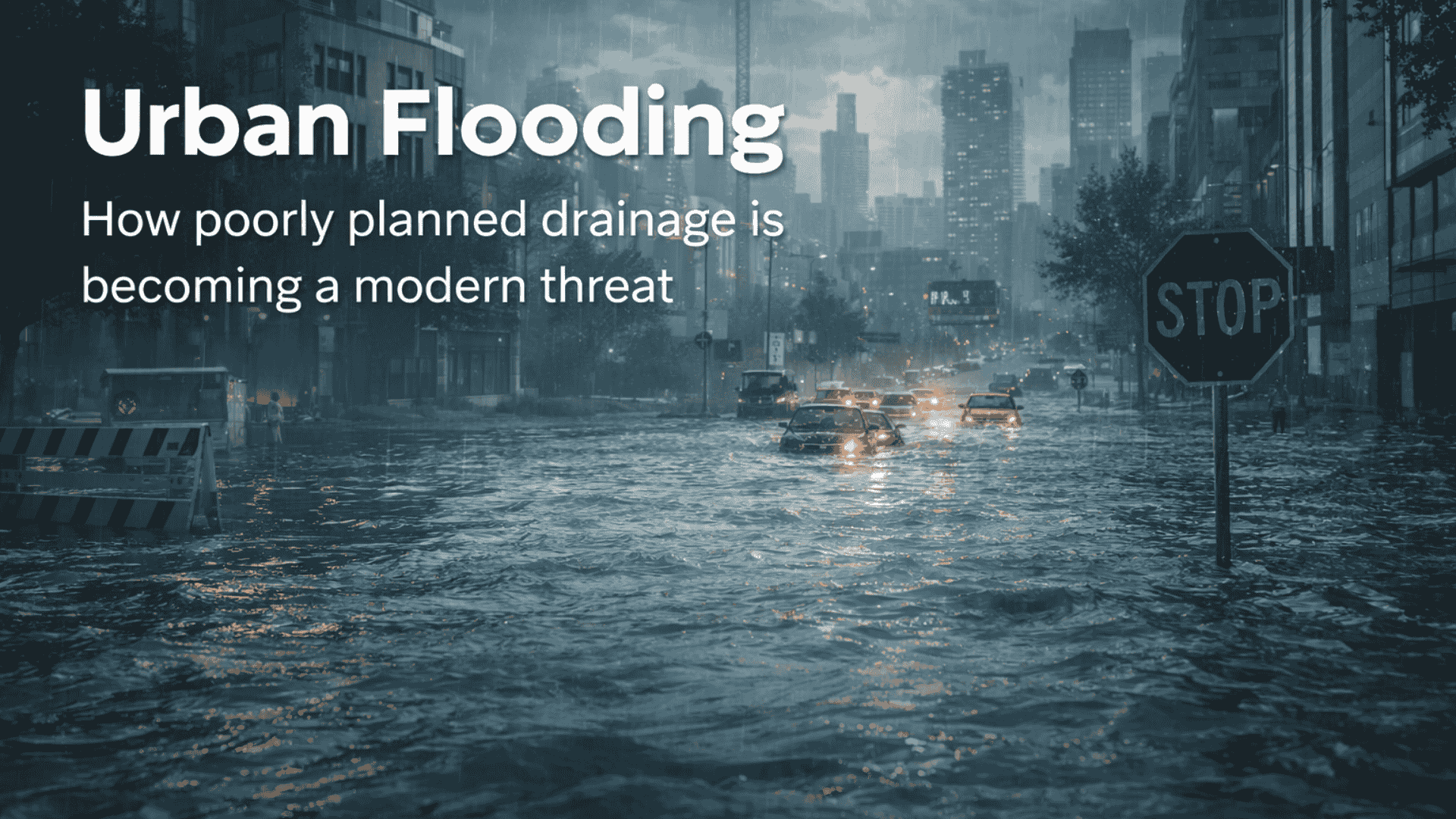

06 Feb Urban Flooding: How poorly planned drainage is becoming a modern threat

Urban flooding has transitioned from a seasonal nuisance to a pervasive modern threat, undermining the safety, economies, and resilience of cities worldwide. Once confined to coastal megacities or deltas, floods now sweep through inland capitals, overwhelmed by intense rainfall, inadequate drainage, and haphazard urban development. The capital of Nepal, Kathmandu, stands as a stark example of these converging pressures. Its recent experiences illustrate how rapidly growing cities with poorly planned infrastructure are becoming especially vulnerable in an era of climate change and unchecked urban expansion.

Across the globe, the scale and severity of floods have escalated in recent years. In 2024, Europe experienced its most widespread flooding in over a decade, impacting 30 % of its river systems, killing at least 335 people, and affecting more than 410,000 people, which indicates how extreme rainfall events have intensified with a warming climate.

Another example

Kathmandu and its surrounding valley are no different. In late 2024, torrential monsoon rains, some of the heaviest recorded in nearly half a century, overwhelmed the city’s drainage systems, rivers, and tributaries, leaving large sections of the metropolitan area submerged and infrastructure shattered. In late September 2024, the Government of Nepal reported at least 224 deaths, 158 injuries, and 28 missing people due to flooding, including at least 37 in Kathmandu.

What Causes Urban Flooding?

Urban flooding arises from a combination of climatic, hydrological, and human factors:

Firstly, climate change is intensifying rainfall and increasing its unpredictability. Scientific analyses of recent extreme rainfall events in Nepal have shown that such heavy downpours are now significantly more likely due to a warmer atmosphere holding more moisture.

Secondly, rapid urbanization without adequate planning has transformed Kathmandu’s natural landscape. Between 1990 and 2020, built-up areas in Kathmandu and Lalitpur expanded by nearly 386%, while forest cover in the valley declined by approximately 28%. Such unchecked development has replaced absorbent soil with concrete surfaces, increasing surface runoff, and overwhelming existing drainage systems.

Thirdly, many settlements in and around Kathmandu have encroached upon historic flood plains and river corridors. These areas, which once provided natural buffers and channels for floodwaters, now host dense housing and infrastructure, thereby increasing both exposure and risk.

The Impacts of Urban Flooding

The consequences of flooding in Kathmandu have been multifaceted and severe. Beyond the tragic loss of life and injury, the economic toll is staggering. According to government reports, the late-season floods caused damage estimated at nearly NPR 46.7 billion across infrastructure, agriculture, health, and education sectors. Roads, bridges, water systems, and power networks suffered serious damage, disrupting essential services. Thousands of families were displaced, and hundreds of schools and hospitals faced operational challenges due to flooding.

Urban flooding also has longer-term socioeconomic consequences. Floodwater contaminates water supplies, creates risks of water-borne diseases, disrupts businesses, slows economic activity, and erodes public confidence in local governments’ ability to protect communities. In Kathmandu, where dense populations rely on a limited transportation network, even short episodes of inundation paralyze mobility and access to critical services.

Building with Nature in Mind

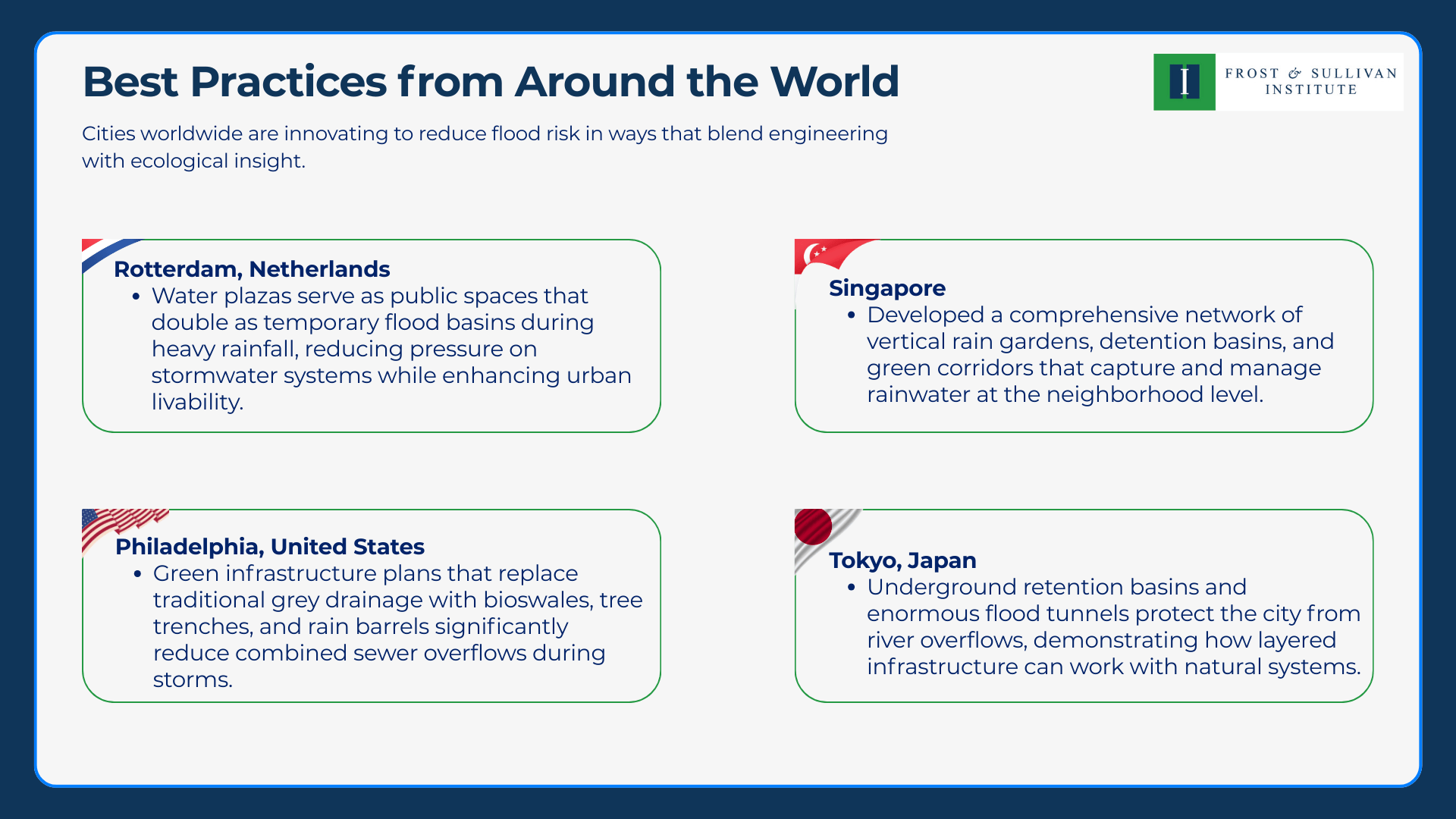

To address urban flooding effectively, cities must pursue strategies that integrate natural systems into urban design rather than rely solely on engineered channels that are easily overwhelmed.

- Preserving and restoring natural waterways and floodplains is crucial. Where rivers once flow freely, restoration can provide space for excess water during storms, relieving pressure on artificial drainage systems. Similarly, protecting forests and green spaces enhances soil absorption and reduces rapid runoff.

- Increasing permeable surfaces within cities, such as green roofs, rain gardens, and permeable pavements, allows rainwater to infiltrate the ground rather than cascade into streets and sewers. In Kathmandu, expanding such features would counterbalance the extensive impermeable concrete that currently dominates the valley floor.

- Moreover, modern urban planning must prioritize climate-adapted infrastructure, including drainage systems designed for higher intensity rainfall patterns than those of the past. Urban planners can leverage hydrologic and hydraulic modeling to predict where pressures on drainage will peak and reinforce these zones proactively.

Importantly, many of these approaches share a central ethos: treating water not as a nuisance to be routed away as quickly as possible, but as a resource to be managed within the city’s ecological and built fabric.

Conclusion

Urban flooding, as exemplified by the recent tragic events in Kathmandu, is not merely a consequence of extreme weather; it is a symptom of deep challenges in urban governance, planning, and environmental stewardship. Without fundamental shifts toward resilience and sustainability, flood risks will only grow as populations expand and climate change intensifies. However, by learning from global best practices and restoring natural hydrological functions within the urban landscape, cities can reduce vulnerability and safeguard their inhabitants. Kathmandu’s experience offers a compelling case for urgent reform, not only in Nepal, but in all cities confronting the rising tide of urban flooding.

Blog by Shreya Ghimire,

Research Analyst, Frost & Sullivan Institute