03 Feb Wastelands to Wonders: World’s Landfills Crisis and India’s Emerging Success

At the edge of our cities, where roads thin and zoning laws lose interest, the land begins to rise in unnatural ways. These are not hills shaped by geology, but by habit, layers of plastic, food waste, broken concrete, electronics, batteries, clothe and other consumer goods. Landfills are often described as endpoints, the final stop for things we no longer want. In reality, they are long-term liabilities embedded into urban systems.

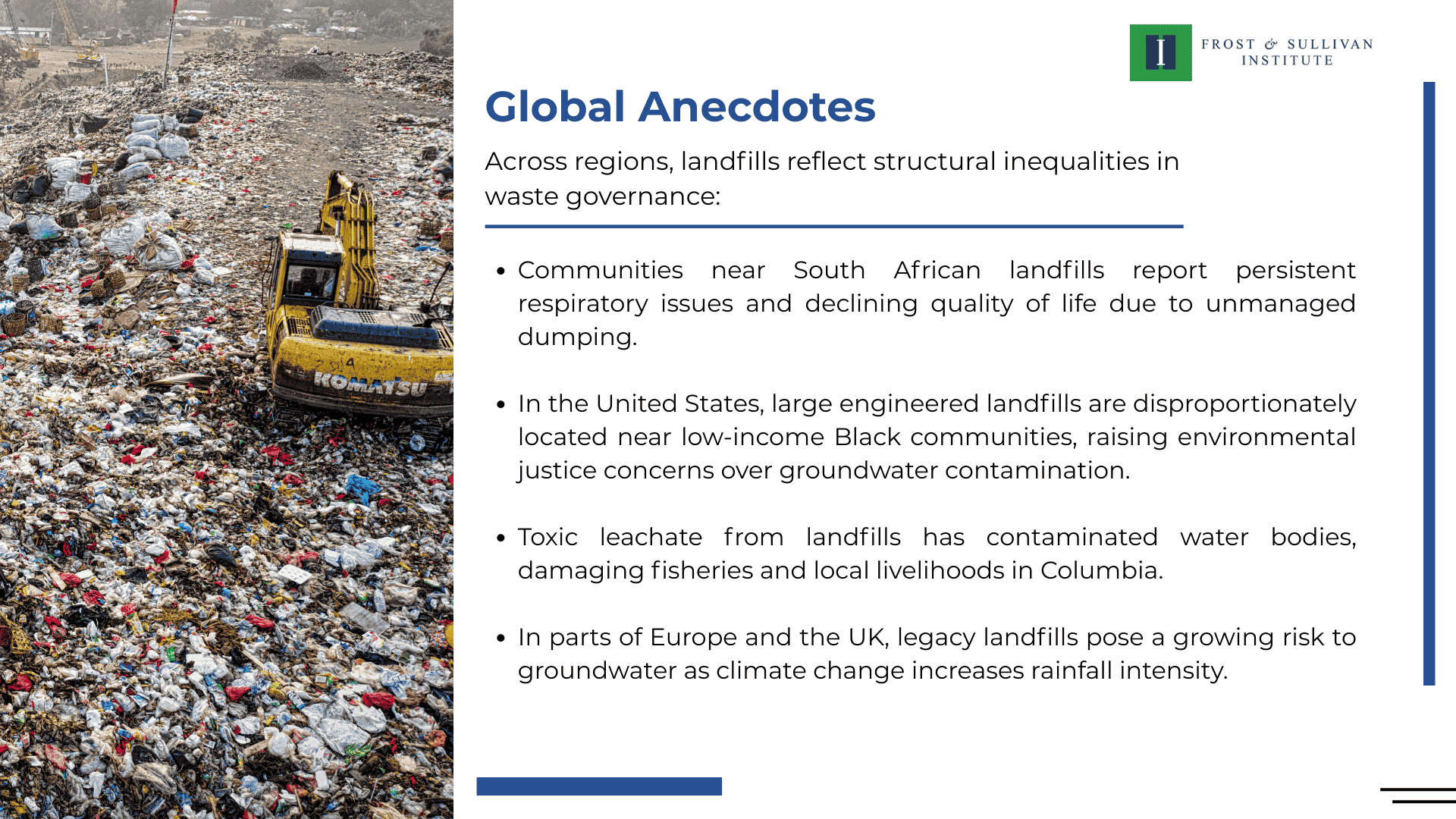

For communities living nearby, landfills are not abstract environmental issues. They affect air quality, groundwater, public health, and land use for decades. As cities expand and consumption increases, the amount of waste produced also increases. It seeps into ecosystems, budgets, and climate systems, turning local disposal sites into global risk points.

A Global Problem Hidden in Plain Sight

The scale of the global landfill crisis is growing faster than urban infrastructure can manage. The World Bank estimates that the world generates over 2.01 billion tons of municipal solid waste annually, which is expected to rise to 3.8 billion tons by 2050 if current trends continue. Nearly 40% of this waste is dumped in landfills or open dumps, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where waste systems struggle to support rapid urbanisation. These numbers are not just about disposal. For cities, it is:

- Rising land scarcity, as dumps expand outward,

- Rising public health costs from air and water contamination, and

- Long-term climate exposure due to methane emissions from decomposing organic waste.

Despite growing awareness, only 20% of the world’s waste is recycled. This means that cities are stuck with landfill-dependent systems that are expensive to maintain and hard to reverse.

Why Landfills Harm More Than We Think

Beneath every landfill lies a slow chemical reaction. Organic waste decomposes anaerobically, producing methane, a greenhouse gas over 80X more potent than CO₂ in the short term. Liquids percolate downward, forming leachate, a toxic mix of heavy metals, pathogens, and chemicals that contaminate soil and groundwater.

As climate risks intensify and cities densify, landfills operate as delayed environmental liabilities. Managing them is no longer just a sanitation issue; it is a strategic urban and climate imperative.

Urban flooding also has longer-term socioeconomic consequences. Floodwater contaminates water supplies, creates risks of water-borne diseases, disrupts businesses, slows economic activity, and erodes public confidence in local governments’ ability to protect communities. In Kathmandu, where dense populations rely on a limited transportation network, even short episodes of inundation paralyze mobility and access to critical services.

Waste Mining: Reframing Landfills as Resource Deposits

As the true cost of landfills becomes impossible to ignore, a new idea is reshaping waste management and waste mining. Instead of sealing landfills, waste mining treats them as urban resource deposits. Waste mining involves excavating legacy waste, separating materials mechanically, and recovering usable plastics, metals, aggregates, and fuel. This approach simultaneously addresses land scarcity, emissions, and material shortages. India has emerged as a notable testing ground for this shift.

India’s Emerging Models

At the Bhalswa landfill in Delhi, Vipul Singh, founder of the Tapas Foundation, has pioneered an initiative that turns legacy waste into construction material. Through the recovery of construction and demolition debris buried in the landfill, Singh developed “Dumpcrete”, upcycled bricks and blocks made from reclaimed aggregates. By transforming inert waste into building materials, Dumpcrete reduces reliance on virgin sand and stone, cuts emissions associated with traditional brick kilns and diverts waste from landfills permanently. The initiative has already upcycled over 100 tons of waste into tens of thousands of eco-bricks, demonstrating how circular construction can emerge directly from landfill remediation.

If Bhalswa represents grassroots innovation, few transformations are as dramatic as Perungud. Once a 226-acre dumpyard, the site is undergoing large-scale biomining led by the Greater Chennai Corporation with partners such as Blue Planet Environmental Solutions. To date, authorities have processed over 48.4 lakh tons of legacy waste, reclaiming around 96–100 acres of land. Materials recovered through biomining have been repurposed into urban furniture, paving blocks, recycled glass vessels, steel products, and landscaping soil. Plastic waste has been converted into benches and public infrastructure, while refuse-derived fuel has replaced fossil fuels in industrial kilns, avoiding nearly 56,000 tons of CO₂ emissions. Perungudi is no longer just a cleanup project, it is an experiment in urban regeneration, where waste is transformed into civic value. Blue Planet is now working on another landfill in Chennai’s Kodungaiyur region, which is three times the size of Perungudi. If successful, it will become one of India’s largest-ever landfill reclamation projects.

These initiatives signal a shift from waste disposal to urban regeneration.

From Waste to Worth

Landfills reflect how societies manage growth, consumption, and responsibility. India’s experience shows that even the most degraded waste sites can be reintegrated into urban systems when policy intent, technology, and scale align. The global challenge is no longer whether landfills are a problem, but whether cities are prepared to transform them from long-term liabilities into sources of environmental and economic benefit.

Blog by Samyuktha Purusothaman Nair,

Research Analyst, Frost & Sullivan Institute