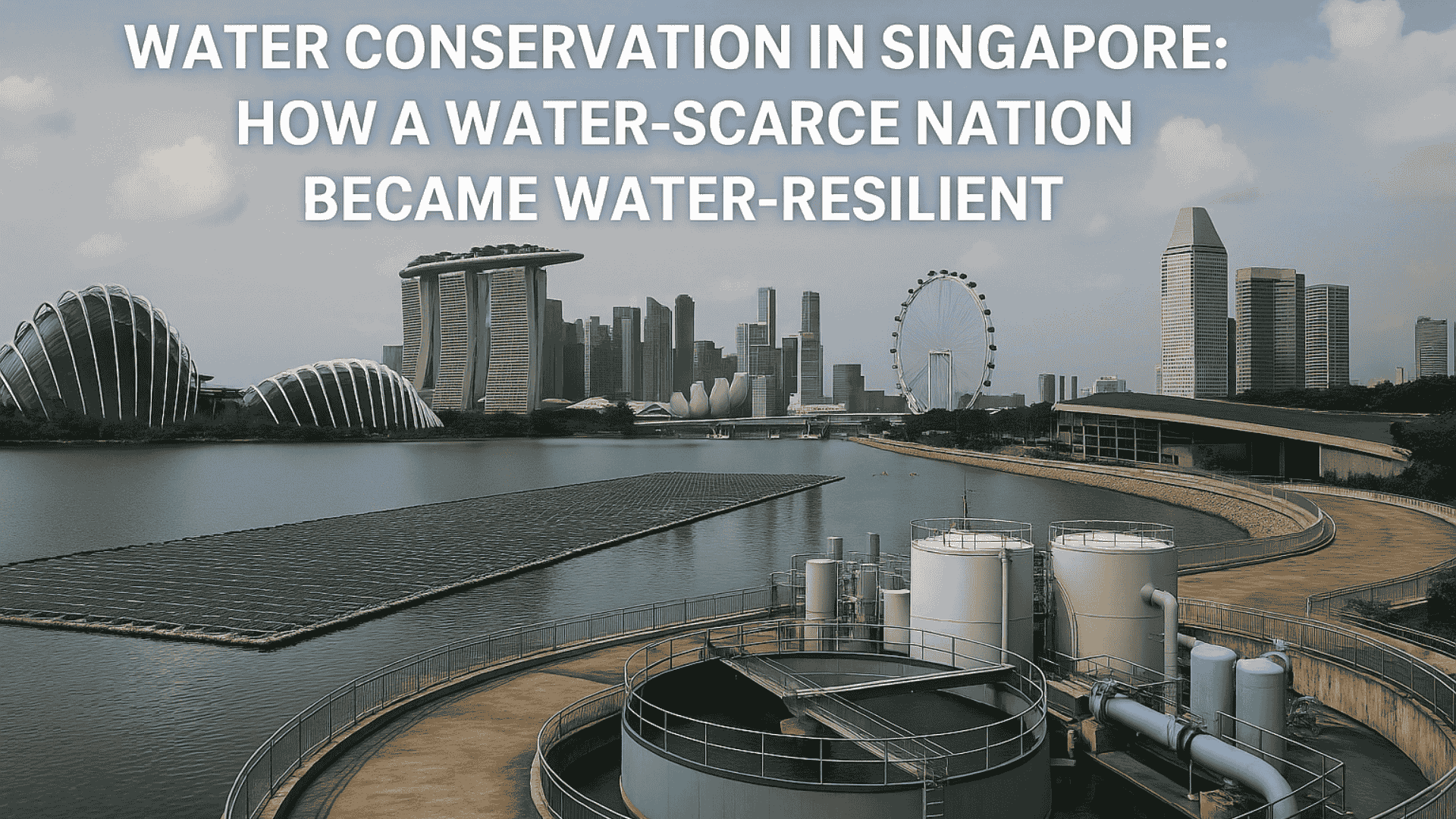

07 Nov Water Conservation in Singapore: How a Water-Scarce Nation Became Water-Resilient

The Global Crisis of Water Scarcity

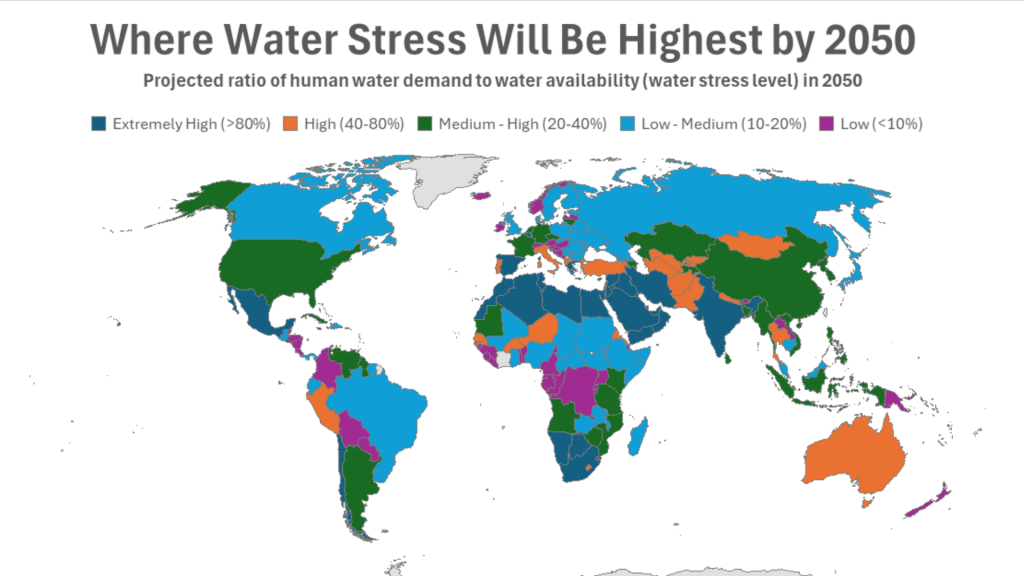

Water scarcity has emerged as a defining global challenge of the 21st century. Rapid population growth, urbanization, industrial expansion, and climate change have intensified pressure on freshwater resources. According to the United Nations, approximately 2.3 billion people live in water-stressed countries, with nearly 4 billion experiencing severe water scarcity for at least one month each year. These pressures have far-reaching implications for public health, food security, sustainable development, and political stability.

Source: World Resources Institute

Water scarcity is not solely a problem of physical supply, but often of poor management, inadequate infrastructure, and unsustainable usage patterns. It is in this context that Singapore, a small, highly urbanized island nation with no natural aquifers and limited land offers a globally relevant model of resilience. Despite being one of the most water-constrained countries in the world, Singapore has developed a comprehensive and technologically advanced water management system that ensures both sufficiency and sustainability. This transformation did not occur overnight but is the result of decades of planning, investment, and public engagement.

Singapore’s Water Vulnerabilities and Strategic Response

Singapore’s vulnerability to water scarcity is rooted in its geography. The country has no large rivers or groundwater sources and receives substantial, yet highly variable, rainfall. In the early decades of its independence, it relied heavily on water imported from Malaysia under a series of long-term agreements. While these agreements provided temporary relief, they were geopolitically fragile and could not guarantee long-term water security.

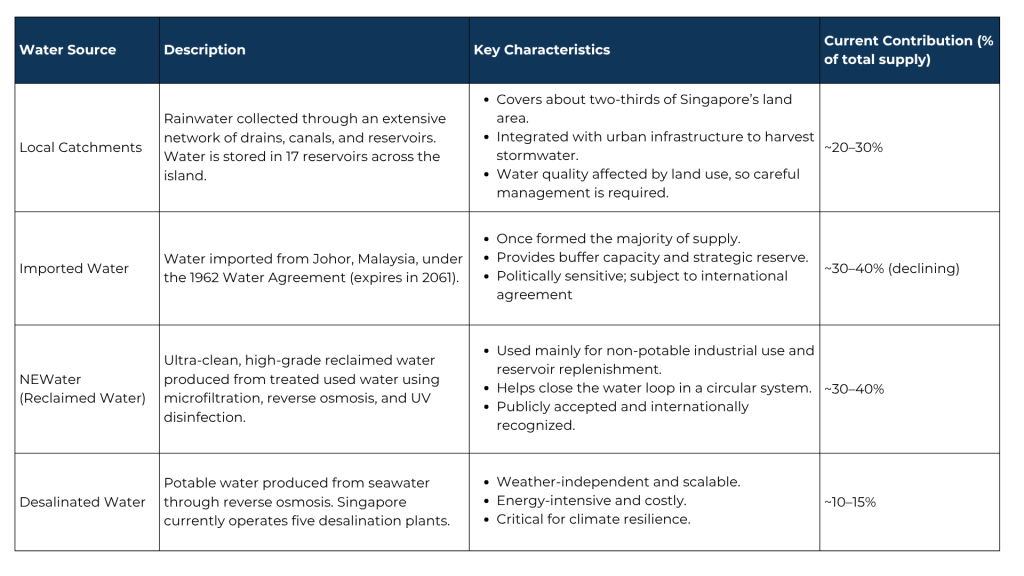

Recognizing these vulnerabilities, Singapore embarked on a multi-pronged strategy to secure its water future. Central to this strategy was the development of what is now termed the “Four National Taps”, a diversified water supply framework comprising: water from local catchments, imported water, highly treated reclaimed water branded as NEWater, desalinated water.

Each of these “taps” serves a distinct function in Singapore’s water system. Local catchments help to harvest rainwater in reservoirs and canals; imported water provides buffer capacity (though with a planned phase-out); NEWater is used both for industrial purposes and indirectly for potable use; and desalination offers a weather-independent source that strengthens overall resilience.

Infrastructure and Institutional Innovations

Singapore’s water transformation has been underpinned by infrastructural development and a strong institutional framework, led by the Public Utilities Board (PUB), the national water agency. One of the most significant infrastructural projects is the Deep Tunnel Sewerage System (DTSS), an underground network that channels used water via gravity to centralized reclamation plants. From there, water is treated and either discharged or recycled through NEWater facilities. This approach not only improves the efficiency of wastewater management but also enables large-scale reuse. The integration of wastewater treatment and NEWater production in some cases within the same facility reflects Singapore’s emphasis on land optimization and system integration.

NEWater, in particular, is emblematic of Singapore’s technological innovation. Treated through microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet disinfection, NEWater meets World Health Organization drinking water standards and is widely accepted by the public. It currently meets up to 40% of Singapore’s total water demand, a figure expected to rise significantly in the coming decades.

Beyond physical infrastructure, Singapore has also institutionalized long-term water planning. Policies are developed with a 50- to 100-year horizon, anticipating population growth, climate variability, and technological change. This strategic foresight is further reinforced by economic instruments, such as volumetric pricing that reflects the true cost of water production and encourages conservation, along with efficiency labelling for water-consuming appliances.

Four Key Lessons from Singapore’s Approach

Singapore’s success offers several key insights for other countries, particularly those grappling with similar constraints or anticipating future water stress.

- Diversification of Supply Reduces Risk

By moving away from reliance on a single or dominant water source, Singapore has created a flexible supply system. The Four National Taps strategy ensures that if one source is compromised, whether by climate variability, technical failure, or geopolitical tensions, others can compensate.

- Invest in Reuse and Recycling at Scale

Singapore treats water as a circular resource. Its pioneering use of treated wastewater (NEWater) demonstrates that with the right technology and public communication, even highly urbanized societies can adopt potable reuse. NEWater is not only cheaper than desalination but also less energy-intensive and environmentally sustainable.

- Long-Term Infrastructure Planning Pays Off

Major infrastructural projects such as the DTSS are designed to serve the nation for up to a century. This long-term vision allows for the efficient allocation of public funds and minimizes the need for disruptive retrofits. It also enables integration between different parts of the water cycle, increasing operational efficiency.

- Demand Management is as Important as Supply Expansion

Singapore has consistently promoted water conservation through pricing, regulation, and public education. The city-state had succeeded in reducing per capita domestic water consumption from over 160 litres per day in the early 2000s to around 141 litres today, with an ambitious target of 130 litres by 2030. Through campaigns like “Make Every Drop Count,” water conservation has become a shared social value rather than merely a technical or regulatory issue.

Singapore’s experience illustrates that water security in the face of scarcity is not only a question of geography or resource abundance, but of governance, innovation, and public engagement. Its integrated approach combining diversified supply, advanced treatment technologies, infrastructure investment, and behavioral change serve as a model for other water-stressed nations.

While the specific technologies and policies adopted in Singapore may not be directly transferable to all contexts, the underlying principles resilience through diversification, long-term planning, the water reuse cycle, and societal buy-in are broadly applicable. As climate change intensifies and freshwater scarcity becomes more acute globally, the Singapore model offers not only technical solutions but a powerful narrative of what is possible when water is treated as a strategic, national priority.

Blog by Shreya Ghimire,

Research Analyst, Frost & Sullivan Institute