18 Sep Why Estonia Is Europe’s Digital Powerhouse: A Study in E-Governance Transformation

E-Governance as the Future of Government

Modern governance faces increasing pressure to provide services that are fast, transparent, and resilient. Traditional bureaucratic systems that are fragmented, paper-based, and often opaque are becoming less compatible with digital society. Citizens now expect governments to operate with the same efficiency, accessibility, and user focus as digital platforms in the private sector. In this context, e-governance has become a structural necessity.

E-governance refers to the reorganization of public administration, in which citizen data, administrative processes, and inter-agency coordination are automated, secure, and user-centered. Countries that invest in these systems stand to benefit from reductions in administrative costs, higher citizen satisfaction, and improved trust in public institutions.

As of 2024, over 73% of countries globally have initiated e-government reforms, but very few have integrated these systems across the entirety of the public sector. This is where Estonia stands apart.

Digital infrastructure in today’s world defines how a society organizes power, trust, and access. At its core, digital infrastructure encompasses systems such as secure data exchange layers, digital identity frameworks, and interoperable platforms that enable seamless interaction between citizens, businesses, and government. For society, this shift has profound implications: it can reduce inequality in service access, empower individuals with control over their data, and create a more transparent, responsive public sector. Estonia’s transformation demonstrates that when digital infrastructure is treated as a foundational public good akin to roads or electricity, it becomes a multiplier of civic engagement, economic productivity, and institutional resilience. In this context, digital infrastructure is not just about faster services; it’s about reimagining the social contract for a digital age.

Why Estonia?

Estonia is not chosen for its size or geopolitical weight, but for the depth and coherence of its digital transformation. With a population of just 1.3 million, Estonia operates what is arguably the most comprehensive digital government in the world. In contrast to other digitally ambitious nations such as Denmark, Singapore, or South Korea, Estonia’s case is unique because an individual can complete tax filing in under 3 minutes, register a business in under 15 minutes, and vote in national elections online, all without setting foot in a government office.

- It is fully integrated: Estonia became the first country to declare 100% of government services digitalized in 2024.

- It operates on principles, not just platforms: Core architectural ideas such as the “once-only” principle, data sovereignty, and citizen transparency are embedded into law and code.

- It is exportable: Estonia actively shares its model through the e-Governance Academy, which has supported over 60 countries in digital transformation.

While many countries implement partial or project-based digital initiatives, Estonia has institutionalized digital governance as the de facto mode of operation.

Defining E-Governance: Estonia’s Interpretation

In academic literature, e-governance often encompasses four dimensions: service delivery, internal administration, democratic participation, and inter-agency coordination. Estonia’s model integrates all four through a single interoperable ecosystem built on:

- Digital identity (e-ID) issued to 99% of the population,

- The X-Road data exchange layer, enabling secure data queries,

- Legal infrastructure that mandates the once-only collection of citizen data.

More than a technological upgrade, this model redefines the state-citizen relationship where citizens interact with government not as passive recipients of services, but as active owners of their data and experiences.

The Benefits: Quantifying the Gains

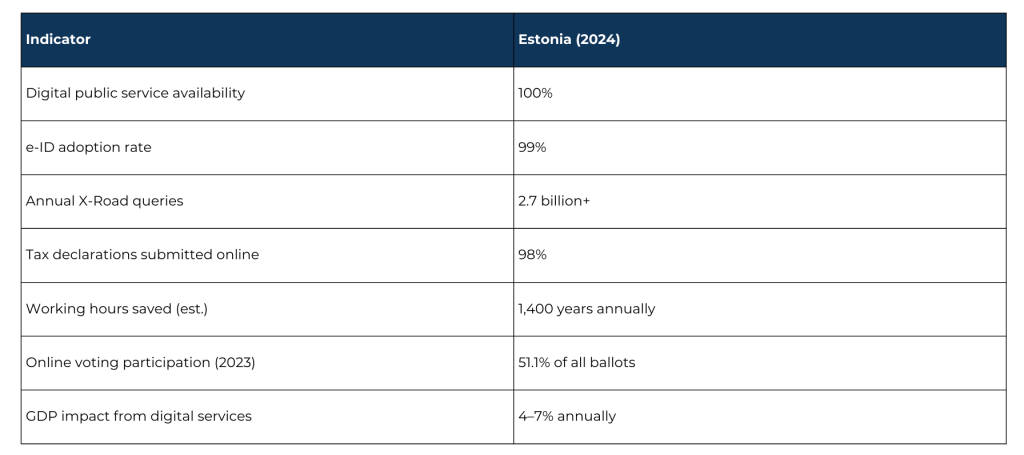

Estonia’s e-governance achievements are measurable. Below are key indicators of national-scale outcomes:

These metrics demonstrate that e-governance is not a cost center, but an economic enabler. The E-Residency program alone has contributed over €13 million in socio-economic benefit, including tax revenue from foreign-owned digital companies.

What Can Be Learned: Practical, Transferable Practices

Rather than offering a menu of policies, Estonia presents a strategic architecture that other countries can adapt. Three key practices stand out:

5.1. Legal and Ethical Foundation for Digital Identity

Estonia’s digital transformation began with legislation. The Digital Signatures Act of 2000 established legal equivalence between handwritten and digital signatures, giving rise to a secure, interoperable national ID system. This trust framework enabled everything that followed like authentication, voting, health records, taxation, while preserving privacy and consent. Hence, Digital transformation must begin with law, not just code.

5.2. Data Interoperability via X-Road

At the core of Estonia’s governance model is X-Road, a decentralized data exchange system that allows public and private entities to interact securely. All data access is logged, and citizens can audit who viewed their records. The result is both efficiency and accountability. In 2024, the system handled over 2.7 billion data queries, reducing redundancies and eliminating paperwork across agencies. A scalable, secure interoperability layer is essential for system-wide digital government.

5.3. Proactive and Citizen-Centered Service Delivery

Estonia is pioneering proactive governance, where services are not just accessible but they are anticipated. For example, when a child is born, the government automatically initiates child-support benefits and offers pre-filled applications for parental leave, without requiring citizen requests. So, true e-governance is not reactive digitization but predictive, user-centered design.

Conclusion

Estonia’s transformation from post-Soviet state to digital vanguard illustrates that e-governance is not a luxury of scale or wealth; it is a function of vision, design, and political will. The Estonian model is neither perfect nor universally replicable in every detail, but it provides a coherent, measured, and strategic framework for rethinking the architecture of public service.

As governments around the world confront climate crises, migration flows, and political distrust, the Estonian case suggests that the digital state is not just more efficient; it may be more resilient and more democratic.

Blog by Shreya Ghimire,

Research Analyst, Frost & Sullivan Institute